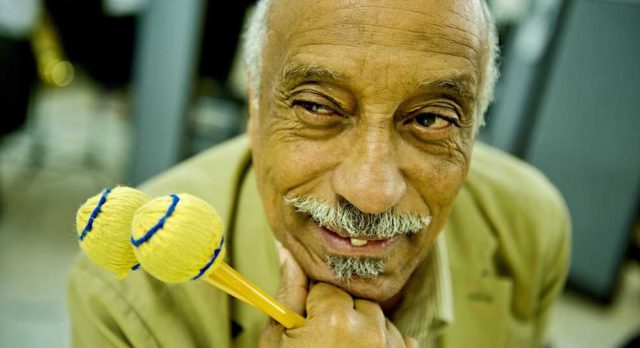

50 years ago he was the first African who graduated from the Berklee School of Music. As an arranger and composer, he integrated pentatonic Ethiopian scales into jazz harmony and created unique style known as Ethiojazz. His fans include Robert Plant, his music was used by Jim Jarmusch in his film Broken Flowers. His most famous song "Yegelle Tezeta" reveals the hidden link between Ethiopia and the blues.

In 2008, The Barbican, and then Glastonbury, hosted a concert featuring four of Ethiopia’s most famed musicians, key artists from what is now seen as the country’s “golden period” of music, crystalising in the last days of Haile Selassie, before finally being silenced as Mengistu’s ‘Derg’ administration quashed the country for nearly two decades. Mahmoud Ahmed had played the country a handful of times, his still powerful vocal garnering him a Radio 3 World Music Award. Gétachèw Mèkurya, an octogenarian saxophonist whose timbre and technique is considered by some to pre-figure Ornette Coleman’s ‘free’ experiments by several years, has enjoyed a new lease of life in Europe, hooking up with avant-punks The Ex. Alèmayèhu Eshèté, initially taking his lead from Elvis Presley, had never performed in the UK, though he plays regularly for the ex-pat Ethiopian community in the US. The last of the four, Mulatu Astatké, whose unique music punctuated Jim Jarmusch’s film, ‘Broken Flowers’, is in many ways the most crucial figure in the country’s recent musical history. He had played the UK for the first time in over 15 years just beforehand at Cargo in April 2008 with London-based collective The Heliocentrics for Karen P’s ‘Broad Casting’ session, a gig that has culminated in a unique new album for Strut Records’ ‘Inspiration Information’ studio collaboration series.

“Being away for a long time from the UK, I really thought people had forgotten about or hadn’t heard of Mulatu,” he states. “At Cargo, there were so many younger guys giving me that beautiful warm reception. They really loved my music and the band. For the musicians to learn the Ethio-jazz classics like that in a day was incredible. I have a lot of attraction to the UK – I feel like I almost grew up here during my teens. I love the chance to come over and play. It was an excellent experience.”

It has taken Astatke over forty years to start to attain the recognition he deserves. Born in 1943 in Jimma, Ethiopia, he came over to North Wales at the age of 16 to continue his further education, focusing initially on the sciences. Music quickly caught his attention, and he was encouraged to pursue it by one of his teachers. “I tried trumpet, I tried clarinet, keyboard – I was playing everything there,” he recalls. “After I finished school, I went to Trinity College in London. I started playing different clubs. I used to hang out with Tubby Hayes, Frank Holder, Joe Harriot and Ronnie Scott. It was a beautiful time.”

This was around 1957, the era of ‘London Is The Place For Me’ captured so astutely on the four Honest Jons compilations that document the ensuing musical shifts that happened in the wake of the SS Windrush. “When I was in England, I started seeing people coming from Ghana, Nigeria, Trinidad, trying to promote and expose their music to a European audience,” says Mulatu. “They had a connection with England because of the Commonwealth. That also influenced me to concentrate on promoting Ethiopian music. It was with that feeling that I went to America.”

For many Afro-American artists of the era, ‘Africa’ was a signifier; a metaphor and an aspiration as much as a destination. Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef and Randy Weston studied and played there, bringing a freshness to their music on their return. Conversely, Nigerian Babatunde Olatunji, whose percussion leant itself so memorably to Art Blakey and Max Roach amongst numerous others, made the opposite journey, educating many musicians in the US to understand the roots of his music.

The industrial and cultural strength of America ensured that their music was re-appropriated in the most intriguing places. Mulatu’s story in many ways underlines one of the core themes of 20th Century music, of how increased globalisation and communication have sped up the process by which ideas are exchanged and new developments evolve. It is also a bitter irony that colonialisation and the slave trade, surely the global economies’ darkest underbelly, meant that newly independent African countries had the language and international links to spread their creative ideas.

“For many years Ethiopia was a very closed country and we never had this access of promoting our music and culture,” states Mulatu. “I wanted to create something so I could be identified like those musicians I’d seen in England.” Mulatu continued his studies at Berklee College in Boston in 1958 (he was their first ever African student) before moving to New York, forming a group called The Ethiopian Quintet, around 1963. The band consisted of himself and Afro-American and Puerto Rican musicians, and they recorded two volumes entitled ‘Afro-Latin Soul’. Combining Ethiopian melodies with 12- note harmonies and Western Instrumentation, his idea was also to underline the African roots of Latin music – “it was during the ‘60s that ethio-jazz came to life,” he remembers. “one night we’d be playing a jazz club in New York, the next a Puerto Rican wedding North of the Big Apple.”

In the radical musical scene of the Sixties, he met and hung out with John Coltrane, who was intrigued to meet an African musician blending music in this fashion. “I met him in Birdland and sat and talked to him for a while. He was so happy to discuss, really, with an African musician. Coltrane was a cool guy – very peaceful. That was my impression.” Mulatu later recorded an album with Coltrane’s second wife, Alice, when she visited Ethiopia, though the tapes were sadly lost during the destructive atmosphere of the Derg.

After gigging around New York, he returned to Addis in the late ‘60s and collaborated with Poet Laureate Gabre-Medhin and even composed for the poet’s stage works. He continued to set about making new arrangements of traditional Ethiopian melodies and songs and was soon crowned the ‘Father of Ethio-jazz’. Mulatu’s approach was a radical one, especially for those musicians who had worked for Army and Police bands. As Addis nightlife started to throng to the sound of modern Ethiopian pop, a taut funk, soul and jazz hybrid with eerie pentatonic chords, state musicians began to moonlight, and a small home grown recording industry started to blossom, bucking the Emperor’s censorship policies. Duke Ellington would pay a visit in 1973, performing with Mulatu at one of his final live appearances in Africa. This era of creativity would eventually die out as Mengistu’s repressive policies took hold.

At the time of the Derg, Mulatu was a board member of the International Jazz Federation (IJF) an organisation that had links with UNESCO, so this gave him a chance to travel, and offered him a certain amount of freedom. He also took part in the ‘National Black Arts Festival’ in Nigeria, where he presented a music production called ‘Our Struggle’. It was here that he witnessed live shows by Fela Kuti, and Sun Ra, a musician he’s been compared to, and, as it happens, whose trilogy of ‘Heliocentric Worlds’ albums gave Mulatu’s current collaborators their name.

The ‘Ethiopiques’ CD series has since opened a new audience to his ‘Ethio-jazz’ experiments, but it wasn’t until Jim Jarmusch’s ‘Broken Flowers’ film that momentum started to gather, aided further by a ‘Best of…Ethiopiques’ compilation released in 2007. Mulatu’s ‘Inspiration Information’ collaboration with The Heliocentrics can be legitimately seen as the next step in a musical fusion, collaboration and cross cultural blend that began the day young Mulatu arrived in the UK back in the 1950s.

“When we came to the UK for the Ethiopiques gigs at Barbican and Glastonbury, (The Heliocentrics) gave me and Joel Yennior (Either Orchestra) some backing tracks and groove ideas to take away,” continues Mulatu. “By listening to this, you can feel the talents of different musicians from different backgrounds. Ethiopian, British, American. There’s a new composition, ‘Cha Cha’, and ‘Dewel’, based on Ethiopian Coptic Church music. The band took it and added what they feel. It’s a nice experiment. There’s also ‘Chik-Chikka’, which is a well known traditional Ethiopian folk song.”

Having drawn plaudits from the likes of Jim Jarmusch, Elvis Costello and Robert Plant, it’s a good time for Mulatu and the other musicians who toughed it out, and we can finally see this unique music as not austere, standing out on its own, but as a part of the interactive whole, that has produced some of the most gripping music in the latter part of the 20th Century.

“It’s like going back to the feel of the late ‘60s, it really feels like that,” he concludes. “My own music has taken a very different direction with Ethio-jazz. This album is mainly about tracing roots using the original Ethio-jazz sound as a solid base. Tracing roots is no bad thing, it’s great for the development of the music. And it has been great working with these guys. They are all great players.”

2009 will be an exciting year for Mulatu as the recognition of his music continues to gather pace. He is continuing his long running and valuable lecturing work as an artist-in-residence at M.I.T. in Boston, flying the flag for Ethiopian music, its heritage and the unsung influence that it has had on many forms of Western music. “There are many elements that pre-date classical music by many years – the Meqyammia which is a conducting stick used in 360 AD and the Kabaro, similar to a timpani drum and used in the same way, less as a time-keeping instrument, more as a feature of a composition. This again was part of church music originating from 360 AD. Relating to jazz, the Derashe tribe in Southern Ethiopia managed to play a diminished scale by cutting different sizes of bamboo. You can hear Charlie Parker, even Debussy using these scales. The Derashe used it in their music well before the advent of jazz or classical music.”